The Pilatus Railway

Pilatus (also often referred to Mount Pilatus) is a mountain massif overlooking Lucerne in Central Switzerland. It is composed of several peaks, of which the highest (2,128 m) is named Tomlishorn and is located about 1.3 km (0.81 mi) to the southeast of the top cable car and cog railway station. The two peaks right next to the stations are called Esel (Donkey, 2,118 m), which lies just east over the railway station, the one on the west side is called Oberhaupt (Head-Leader, 2,105 m). Jurisdiction over the massif is divided between the cantons of Obwalden (OW), Nidwalden (NW), and Lucerne (LU). The main peaks are right on the border between Obwalden and Nidwalden.

The top can be reached with the Pilatus Railway, the world’s steepest cogwheel railway, from Alpnachstad, operating from May to November (depending on snow conditions), and the whole year with the aerial panorama gondolas and aerial cableways from Kriens. Both peaks next to the top stations, Esel and Oberhaupt, can easily be reached also by mass tourism.

The trenolab team visited Mount Pilatus after delivering a lecture at ETH Zurich.

The Pilatus Railway

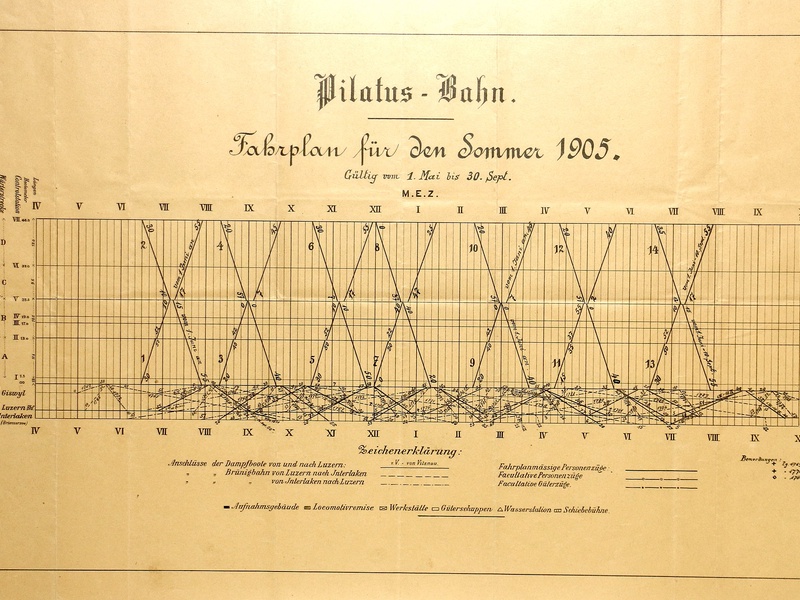

The Pilatus Railway (German: Pilatusbahn, PB) is a mountain railway in Switzerland and is the steepest rack railway in the world, with a maximum gradient of 48% and an average gradient of 35%. The line runs from Alpnachstad, on Lake Lucerne, to a terminus near the Esel summit of Pilatus at an elevation of 2,073 m (6,801 ft), which makes it the highest railway in the canton of Obwalden and the second highest in Central Switzerland after the Furka line. At Alpnachstad, the Pilatus Railway connects with steamers on Lake Lucerne and with trains on the Brünigbahn line of Zentralbahn.

History

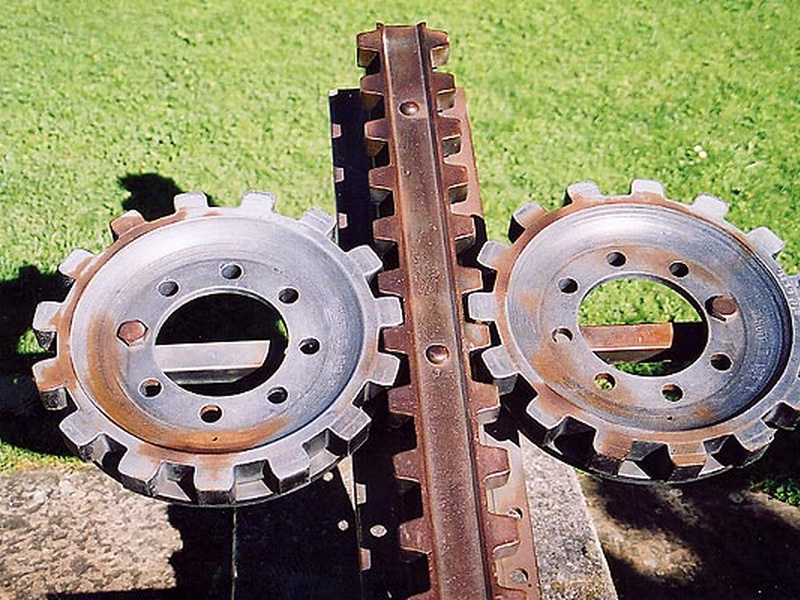

The first project to build the line was proposed in 1873, suggesting a 1,435 mm standard gauge and 25% maximal gradient. It was concluded that the project was not economically viable. Eduard Locher, an engineer with great practical experience, then proposed an alternative project with the maximum grade increased to 48%, cutting the distance in half. Conventional systems at the time could not negotiate such gradients because the cogwheel that is pressed to the rack from above may, under higher gradients, jump out of engagement with the rack, eliminating the train’s driving and braking power. Instead, Locher placed a horizontal double rack between the two rails with the rack teeth facing each side. This was engaged by two flanged cogwheels mounted on vertical shafts underneath the car.

<div class="col-sm-6 col-sm-push-6">

<img src="/blog/20180517_pilatus/slide01.jpg" alt="">

</div>

<div class="col-sm-6 col-sm-pull-6">

<figcaption>

<h4>The Locher system rack and pinion</h4>

The Locher rack system, invented by Eduard Locher, has gear teeth cut in the sides rather than the top of the rail, engaged by two cog wheels on the locomotive. This system allows use on steeper grades than the other systems, whose teeth could jump out of the rack.

</figcaption>

</div>

</div>

This design eliminated the possibility of the cogwheels climbing out of the rack, and prevented the car from toppling over, even under severe crosswinds common in the area. The system was also capable of guiding the car without the need for flanges on the wheels. Indeed, the first cars on Pilatus had no flanges on running wheels, but they were later added to allow cars to be moved through tracks without rack rails during maintenance. The line was opened using steam traction on 4 June 1889, and was electrified on 15 May 1937, using an overhead electric supply of 1550 V DC.

The government provided no subsidy for the construction of the line. Instead, Locher established his own company “Locher Systems” to build the railway. The railway was built entirely with private capital and has remained financially viable throughout its life.

The Pilatus Railway was named a Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers in 2001.

Operation

The line is 4.6 km long, climbs a vertical distance of 1,629 m, and is of 800 mm gauge. Because of the rack-system, there are no conventional points or switches on the line, only rotary switches and traversers. All rails are laid on solid rock, securing rails by high-strength iron ties attached to the rock, without using any ballast.

The line still uses original rack rails that are now over 100 years old. While they have worn down, it was discovered that this can be fixed by simply turning the rails over, providing a new wearing surface that would be sufficient for the next century as well. The cars’ electric motors are used as generators to brake the car during descent, but this electricity is not reused — it is just dissipated as heat through resistance grids. Originally, the steam engines were used as compressors to provide dynamic braking, since the use of friction brakes alone is not practical on such steep slopes.